Rectal Cancer

Definition

Colorectal cancer is the second cause of cancer and death by cancer in Europe and affects just as many men as women.

More than 35,000 new cases are detected each year.

A colorectal tumour can be benign or malignant. A potentially metastatic cancer can spread to other parts of the body.

The cells of the mucous membrane of the colon divide and reproduce in an orderly fashion. A cell can multiply without such controls and form a tumour.

Fortunately, colorectal cancer is avoidable and curable if detected early.

It is a tumour where we have made important progress these last 20 years, thanks to:

- Better Prevention.

- Better Testing.

- Progress in Surgery (Resection of the Rectum by Laparoscopy with TME – Total Mesorectal Excision ) and Chemoradiotherapy, as well as a better multi-disciplinary care.

Causes

Colorectal cancer starts off as polyps (tumours of the colon wall). Not all polyps become colon cancers.

Polyps known by the name of adenomas are the precursors of colorectal cancer.

The risk factors of adenomas and the development of cancer are not fully identified.

Food rich in fats and lacking fibre, getting old, and genetic anomalies are the most well known risk factors.

We are all at risk of contracting a colorectal cancer.

The majority of people who develop colorectal cancer show no signs of any known risk factors.

However, there are illnesses or antecedents which are associated to an increased risk of developing colorectal cancer:

- Diseases which produce chronic inflammation of the colon (ulcerative colitis or Crohn’s disease).

- Family or personal antecedents of colorectal cancer.

- Adenomatous polyps.

- Hereditary syndromes: cases of adenomatous polyposis in the family. Lynch syndrome – HNPCC hereditary non-polyposis colorectal cancer.

Symptoms

Most people with colorectal cancer show no symptoms.

The symptoms of colorectal cancer are often not very specific, you should talk about it to your GP/Family Doctor.

- Changes in bowel movement habits with both constipation and diarrhoea alternately.

- Unexplained anaemia.

- Presence of blood on or in bowel movements which are responsible for the anaemia which generates fatigue.

- Weight loss.

- Abdominal pain similar to intermittent intestinal colic with bloating: it can last for 1 to 2 hours and be followed by a foul bout of diarrhoea (Koenig’s syndrome).

- Sensation of « false needs ».

- More rarely, the diagnosis is made urgently.

The symptoms are linked to an acute complication indicative of an occlusion type tumour (the tumour totally blocks the bowel transit) or a perforation with peritonitis.

Nevertheless, as we have already said, most people, with polyps or colon cancer, show no symptoms.

For this reason, it is very important to regularly take screening tests for colorectal cancer.

Preoperative Chemoradiotherapy

Preoperative radiotherapy is recommended for all stage II and III (stages cT3, cT4 or N+ ) cancers as it reduces the risk of locoregional recurrence.

It helps reduce the size of the tumour and facilitates conservative surgery and reduces by 30 to 50% the lisk of recurrence in the lessor pelvis.

Radiotherapy is also used for tumours which are ineradicable from the outset (fixed).

It is delivered over 5 weeks in association with a concomitant chemotherapy to make it more efficient.

Surgery is programmed 5-6 weeks later.

Traitement Chirurgical

Radiotherapy and chemotherapy are sometimes used as an aid in the preparation for surgery.

Colorectal cancer requires resection surgery (removing the tumour) in nearly all cases, for a complete cure.

Standardised surgical techniques have contributed to improving the rate of conservation of the anus (95%) and reducing the local recurrence rate, as well as the sexual consequences of the surgery, for example difficulty ejaculating and impotency.

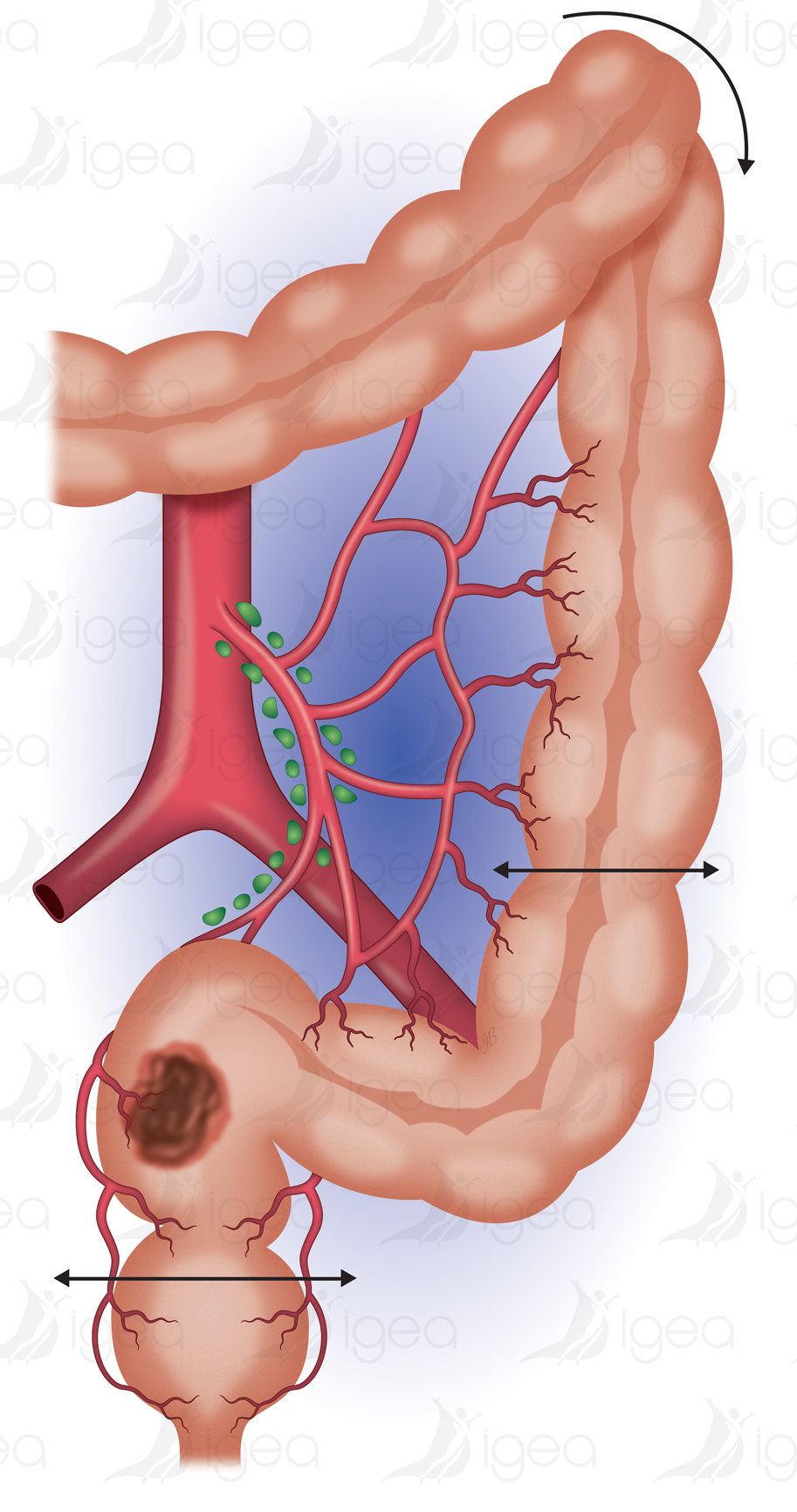

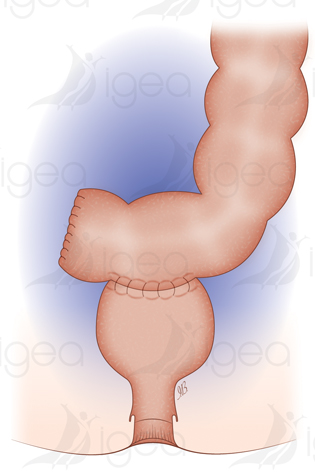

The surgery consists of freeing the left colon and removing the rectum with the tumour and the adjacent ganglions. The liberated left colon is used to re-establish (in 95% of cases) digestive continuity by creating a colo-rectal anastomosis without tensions (suture of the left colon on to the rectum).

This technique is the anterior resection of the rectum with the ablation of the mesorectum, which we normally execute by laparoscopy.

The mesorectum is the fatty tissue around the rectum which contains ganglions. It is delimited by a membrane, the rectus fascia.

It has clearly been proven that the complete removal of the mesorectum (TME-Total mesorectal excision), with a rectus fascia not perforated, reduces the risk of local recurrence.

The quality of the surgery depends on the experience of the surgeon in terms of cancerology and laparoscopy.

Risk of an Ostomy after a previous resection of the rectum.

Thanks to technical progress, less than 5% of patients operated for a colorectal cancer resection have need of an abdominoperineal resection with the definitive installation of a discharge colostomy.

When it is not possible to preserve the anal sphincter, the surgery involves an exeresis of the rectum, the anus and its sphincter (which is the perineal amputation) with the definitive installation of a discharge colostomy (Miles’ intervention).

An ostomy is the joining up of a segment of the intestine (colon >> colostomy ; ileum >> ileostomy) to the skin of the abdomen lateral to the umbilicus (left or right).

The orifice of the ostomy constitutes the artificial anus.

It allows the faecal matter, whose evacuation is no longer controlled by the sphincter of the natural anus, to be collected in a bag.

The ostomy associated with a resection of the rectal cancer is temporary: it is frequently an Ileostomy.

Afterwards it will be closed, subject to the satisfactory healing of the digestive sutures being confirmed by radiological control (opacification without leaks at the level of the colo-rectal anastomosis).

The closing of the ostomy for local accessibility is carried out in a classic manner 6 weeks after the rectal resection.

An earlier closing procedure after 10 days, during the same hospitalisation period, is sometimes possible.

Nevertheless, this ostomy may be definitive if it is carried out in the framework of a cancer situated very low, where the sphincter cannot be saved (a definitive colostomy associated with the amputation of the rectum).

Complications

Rectal surgery may have significant consequences and complications.

The worst complications are those which require further surgery (intervention D):

- For example concerning peritonitis, pelvic abscess, late renewal of bowel movement/occlusion.

- Further surgery to remove the anastomosis or the realisation of a discharge colostomy.

- Haemorrhage.

- Unnoticed injuries to other organs (bladder, urethra, small intestine).

- Mechanical blockage of the support.

- Complications urinating.

- Sexual complications: problems ejaculating and impotency.

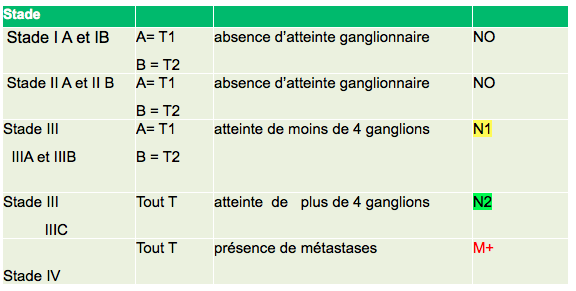

Cancer staging and grading

Once surgically removed, the tumour can be analysed by an anatomical pathologist.

It is graded relative to size and the parietal depth achieved (T), the invasiveness of ganglions (N), and the development of secondary malignant growths at a distance from the primary site (M).

The classification TNM defines the stage of development of the colorectal cancer.

Classification AJCCC :

80 to 90% of patients are cured if the cancer is detected and treated in the initial stages.

This rate drops to 50% or less if the diagnosis is made in the later stages.

Adjuvant Chemotherapy

Post-operative chemotherapy (CT) (or adjuvant chemotherapy) is used when there is a risk of recurrence.

It is used to eliminate cancer cells which might migrate to other parts of the organism.

For patients having received preoperative chemoradiotherapy:

- If the ganglions are not invasive (tumour ypT1-3, N0 at stage I or II) post-operative CT treatment is not useful (as agreed by experts).

- If ganglions are already invasive (stage III where all are pT, N1-2), abstention and post-operative CT are alternatives to be discussed relative to the factors of a bad prognosis (ypT4, N2, perineural invasion of nerves, absence of total excision of the mesorectum).

Prevention

Measures can be taken to reduce the risk of contracting a cancer.

The first consists of eliminating benign polyps by a coloscopy.

As well as eliminating the polyps, the long, flexible, tubular instrument used in this procedure allows a more detailed examination of the colon.

Although it has not yet been proved, it seems that diet can play an important role in the prevention of colorectal cancer.

As far as we know, a diet high in fibre and low in fats is the only nutritional measure which could help prevent colorectal cancer.

Finally, you must be vigilant concerning any changes in your intestinal habits, and make sure that colon examinations are included in your routine medical examinations once you are in the « high risk » group.

Although haemorrhoids cannot lead to a cancer of the colon, they can produce similar symptoms to those of colon polyps or cancer. If you experience such symptoms, please notify your GP/Family Doctor.

Riferimenti bibliografici

- Reference 1 : Test1

- Reference 2 : Test

- Reference 3 : Test

- Reference 4 : Test

- Reference 5 : Test

- Reference 6 : Test

- Reference 7 : Test

- Reference 8 : Test

- Reference 9 : Test