Stomach

Definition

What is cancer of the stomach?

The stomach is a muscular organ in the shape of a sack, located in the superior part of the abdomen. The stomach forms part of the digestive system, which is composed of different organs whose role is to transform food into energy and eliminate the organism’s waste products.

Absorbed by the mouth, food travels along the oesophagus to the stomach, where it is mixed with digestive fluids (enzymes and acids) secreted by the glands which cover the stomach wall. The resulting semi-solid mixture leaves the stomach by an opening surrounded by muscles in the form of a ring, called the pyloric sphincter, and then penetrates the small intestine, then the colon, where the digestion ends.

The stomach wall is made up of four layers.

Cancer of the stomach starts off in the cells of the internal layer, called the mucous membrane. The cancer gradually expands to the other layers of the stomach wall.

Cancers of the stomach which start off in the lymphatic tissue (lymphoma) or the muscles (sarcoma) of the stomach or even in the tissue which supports the organs of the digestive system (gastrointestinal stromal tumour) are less frequent and require different treatments.

Men are more likely to develop a cancer of the stomach than women.

Cancer of the stomach cannot be attributed to a single cause, but certain factors increase the risk of developing the disease:

- A diet rich in salt and smoked or salted meat.

- A diet with few vegetables and fruit.

- An inflammation or other stomach problem, such as:

- Chronic gastritis (prolonged inflammation of the stomach wall).

- Intestinal metaplasia (modification of the cells of the stomach wall).

- Pernicious anaemia (a blood disorder which affects the stomach).

- Previous stomach surgery, below normal production of gastric acid.

- An infection caused by the bacteria Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori), frequently present in the stomach.

- Age, particularly over 50 years old.

- Smoking.

- Family history of cancer of the stomach.

- Professionally being exposed to the treatment of rubber and the production of lead.

Stomach cancer may sometimes develop in the absence of all these risk factors.

Signs and Symptoms

Cancer of the stomach is often asymptomatic during its initial stages.

The most frequent symptom is a slight pain in the abdomen, similar to when you have indigestion.

The other symptoms of cancer of the stomach are generally as follows:

- Loss of appetite.

- Heartburn.

- Indigestion which does not go away.

- Nausea and vomiting

- Feeling bloated after eating.

- Not normal bowel movements.

- Unexplained weight-loss.

- Feeling very tired.

Other health problems may cause certain similar symptoms. Further analyses will help to make a diagnosis.

Diagnosis

After questioning you on the state of your health and having made an examination, your doctor may suspect the presence of a cancer of the stomach.

To confirm the diagnosis, the doctor would also make a few analyses, which would also allow the establishment of the « Stage » and « Grade » of the cancer.

It could be that you must undergo one or more of the following tests.

Blood analyses

Using your blood sample, we check your red blood cells in order to see if you suffer from anaemia (a feeble number of red blood cells) due to the loss of blood caused by a tumour of the stomach.

The samples taken also help to see in what manner your organs function normally and may indicate the possible presence of a cancer.

Test looking for blood hidden in bowl movements

A small sample of your bowel movement is analysed in a laboratory to look for the presence of blood only detectable under a microscope.

Imaging techniques

These techniques provide an in-depth examination of tissue, organs and bones.

X-rays, ultrasound, a CT scan, a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan and a bone scintigraphy, are a number of ways that your medical care team can use to obtain an image of a tumour and check if it is growing.

These tests are generally painless and require no anaesthesia.

You will probably pass a series of X-rays of the oesophagus and the stomach, called an oeso-gastro-duodenal transit or a barium swallow. Where you will be asked to drink a thick chalky liquid, called barium, which will coat the interior of your oesophagus, your stomach and small intestine. The doctor will then be able to better see these organs on the X-rays. If there are signs of a cancer, the doctor can also check if the disease has spread.

Gastro-duodenal fibroscopy (gastroscopy)

The gastro-duodenal fibroscopy helps examine the oesophagus and stomach with the aid of a straight and flexible tube (gastroscope), with a light and camera at the end. Your throat will receive a local anaesthetic, and you will have a mild sedative to help you relax.

To make the examination the doctor inserts the gastroscope into your throat . After the examination you may have a sore throat, which is normal, and will disappear in a day or two.

Biopsy

If the doctor sees something abnormal during the gastroscopy, several samples of tissue can be taken with the help of an endoscope.

This procedure consisting of taking a sample of the cells of the organism in order to examine them under a microscope, is a biopsy.

A biopsy is normally required to establish with certitude the diagnosis of cancer. If the cells are cancerous, the next stage is to determine how rapidly they can multiply.

If further tissue samples are required, the procedure will probably take place under a general anaesthetic.

Extra examinations

If these diagnoses indicate that you have a cancer of the stomach, your doctor may require more blood tests and imagery examinations, or even a laparoscopy, to see if the cancer has spread.

During a laparoscopy, a straight and supple tube with a light and camera at the end, is introduced via a small incision made in the abdomen. After having examined the abdomen, the doctor can take a number of small tissue samples to be sent for histological analysis (biopsy), and remove some lymphatic ganglions.

Stages and classification

Once the diagnosis of a cancer is confirmed, and your medical care team has obtained all the necessary information, it is essential to determine the development Stage and the Grade of the cancer.

Five Stages have been defined for cancer of the stomach. Once the diagnosis of a cancer is confirmed, and your medical care team has obtained all the necessary information, it is essential to determine the development Stage and the Grade of the cancer.

This process of deciding the Stage of the cancer consists of defining the size of the tumour, and checking if it has spread from the site where it started.

Five Stages have been defined for cancer of the stomach:

- Cancer cells are found uniquely in the most superficial layer of the stomach wall (the mucous or mucosa membrane). The cancer at Stage 0 is also called a carcinoma in situ.

- The cancer has spread from the most superficial cellular layer of the mucous membrane to the next layer (submucosa membrane) and the cancer cells have affected 1 to 6 lymphatic ganglions OR the cancer has gained the muscle layer, without affecting the lymphatic ganglions or other organs.

- The cancer has not spread just to the submucosa membrane but the cancer cells have affected 7 to 15 lymphatic ganglions OR the cancer has gained the muscle layer (muscularis propria) and the cancer cells have affected 1 to 6 lymphatic ganglions OR the cancer has propagated to the external layer of the stomach (serosa), without affecting any lymphatic ganglions or other organs.

- The cancer has gained the muscle layer and the cancer cells have affected 7 to 15 lymphatic ganglions OR the cancer has gained the external layer of the stomach and the cancer cells have affected 1 to 6 lymphatic ganglions OR the cancer has gained the adjacent organs, without affecting the lymphatic ganglions or other organs further away.

- The cancer has affected more than 15 lymphatic ganglions OR the cancer has affected the adjacent organs and at least 1 lymphatic ganglion OR the cancer has affected other parts of the body.

The examination under the microscope of the sample taken during the biopsy allows the histological classification (Grade) of the cancer to proceed.

This involves analysing the appearance and comportment of the cancer cells compared to normal cells. The histological classification of the cancer allows the medical care team to have an idea of the future development of the tumour.

We can determine the Grade of stomach tumours by using the Lauren histological classification system. Two Grades are defined for cancer of the stomach: Intestinal or Diffuse.

Intestinal

The cancer cells have an appearance and behaviour very similar to intestinal cells.

However, their growth rate is much slower.

Diffuse

The cancer cells have an appearance and behaviour fairly different to those of normal cells.

They have a tendency to develop rapidly and to expand to other parts of the stomach and body.

It is important to know the Stage and the Grade of your cancer, as this will help you and your medical care team to choose the treatment which suits you best.

Treatment

Surgery

The decision to have surgery depends on the size of the tumour and its location. During the surgery, we will proceed with a partial or total ablation (removal) of the tumour and some of the healthy tissue around it. The surgery will take place under a general anaesthetic, and you will have to stay in hospital for several days afterwards.

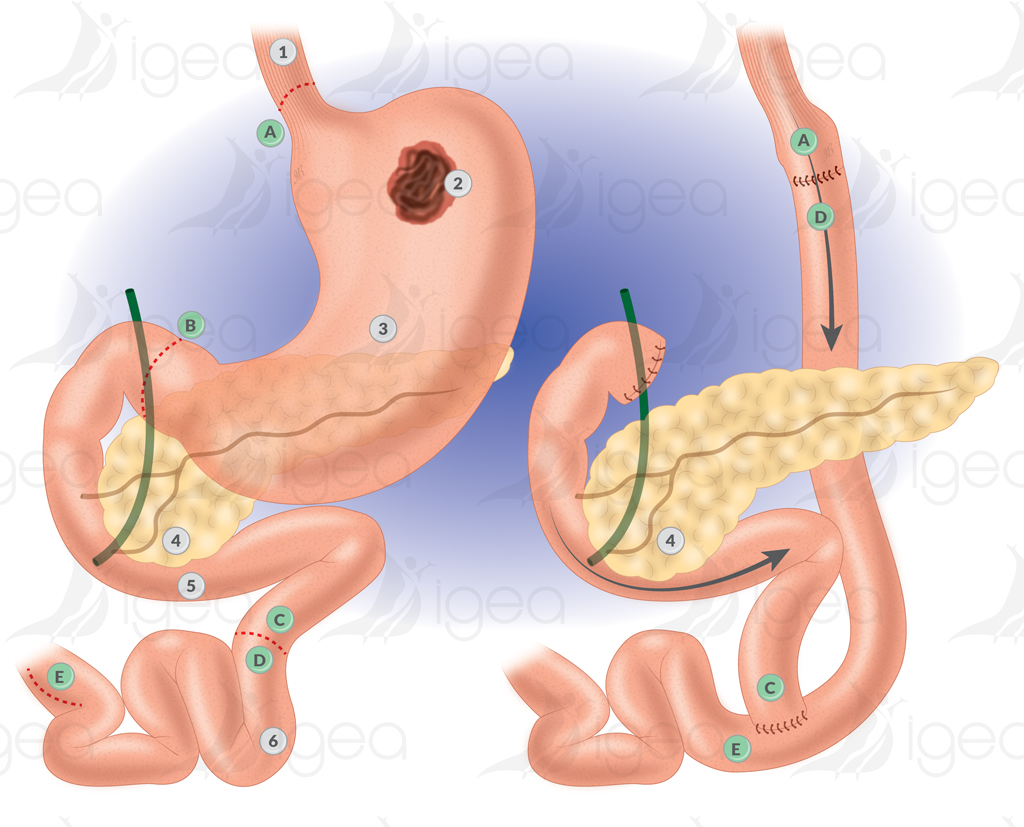

Surgery is the usual treatment for cases of cancer of the stomach. The surgery consists of removing part or the whole of the stomach, and is called a Gastrectomy. The type of Gastrectomy undertaken depends on the Stage of development of the cancer, and whether it has spread or not.

If the cancer is detected early, a partial Gastrectomy could be the only treatment required. The surgeon will, therefore, only remove the cancerous part of the stomach as well as any local lymphatic ganglions.

Depending on the location of the tumour, the surgeon may remove the lower part of the oesophagus or the upper part of the small intestine. Reconstructive surgery can be undertaken at the same time, to fix the remaining part of the stomach to the oesophagus or the small intestine.

In the event of a total gastrectomy, the surgeon will proceed with the total ablation of the stomach, the adjacent lymphatic ganglions, a part of the oesophagus, a part of the small intestine and any other tissue located near the tumour. The spleen may also be removed at the same time. Reconstructive surgery will be undertaken at the same time in order to join the oesophagus to the small intestine.

Palliative surgery does not cure the cancer but may make a patient’s symptoms less severe. If the tumour cannot be removed and it blocks the oesophagus, it is possible to install a hollow tube (endoprosthesis) in the oesophagus to keep it open. This will make it easier for you to eat and swallow.

If an inoperable tumour blocks the passage of food from the stomach to the small intestine, the surgeon can create a new conduit connecting the two organs, in order to bypass the blockage.

After the surgery, it is possible you may experience some pain or nausea. These side effects are temporary and can be reduced.

During the surgery, a feeding tube catheter can be installed into your small intestine in order for you to receive the liquids and nutriments necessary, until you can drink and eat for yourself again. It may be several days before you are capable of drinking again, and eating soft foods.

Eating well and normally after surgery for a cancer of the stomach may be difficult; ask your medical care team to organise for you to see a professional dietician or nutritionist. A personalised diet can be put in place for you to help maintain your health, well-being and quality of life.

Chemotherapy

Chemotherapy can be administered in tablet form or by injection.

Chemotherapeutic medicines inhibit the development and propagation of cancer cells. but they also damage cells which are healthy.

Chemotherapy can also be used in association with radiotherapy (X-rays) to treat cancer of the stomach after surgery. It can also be used to relieve pain or ease the symptoms if the tumour cannot be removed.

Healthy cells can recover with time, but in the meantime, for you, the treatment will perhaps provoke certain side effects such as: skin rashes, or itching skin, nausea, vomiting, loss of appetite, tiredness, hair loss and a higher risk of infection.

Your medical care team can suggest ways of limiting these side effects.

Radiotherapy (X-rays)

With external radiotherapy, a large radiotherapy machine is used to aim the radiation beam precisely at the tumour. The radiation beam damages all cells in its trajectory – normal cells as well as cancer cells. Radiotherapy can also be used in association with chemotherapy to treat cancer of the stomach after surgery. It can also be used to relieve pain or ease the symptoms if the tumour cannot be removed.

The side effects of radiotherapy are generally mild. Perhaps you will feel more tired than usual, you might have diarrhoea, or you notice that your skin has changed at the area treated, and has become red and sensitive to touch. These side effects are the result of the damage suffered by the healthy cells and will go away once the treatment has ended, and the normal cells have regenerated.

How to face up to cancer?

Whatever your situation is, a newly diagnosed cancer, your treatment has already started, or you are a carer for someone who has cancer, you will probably have to find solutions to practical problems, take difficult decisions and manage a whole range of emotions.

Riferimenti bibliografici

- Reference 1 : Test1

- Reference 2 : Test

- Reference 3 : Test

- Reference 4 : Test

- Reference 5 : Test

- Reference 6 : Test

- Reference 7 : Test

- Reference 8 : Test

- Reference 9 : Test